When I came to spend some research time in Georgian England in the past year or two, I realised what an eccentrically horsey place it was. Of course, horses play an important part in the historical documents of the time and also the literature, including Jane Austen’s works. Horses were essential for personal transport and increasingly for public transport. (Thomas Almeroth-Williams’s book City of Beasts is a good place to start.)

Different breeds of horse were emerging to perform new functions, as were new styles of carriage and coach. This was the period in which the Thoroughbred and the first speedy roadsters and trotters began to be produced. Road improvements meant that people could travel further and faster than ever before – weather and health permitting – and the coach horse breeds in particular needed to be fast and enduring to meet some very critical deadlines on the new mail coaching routes. Highwaymen kept up the pace with their own mounts. Hunting squires wanted first class hunters, often with Thoroughbred breeding in them, and agricultural improvements and industrial developments increasingly required bigger, stronger horses to work the land and haul heavy loads.

Georgian eccentrics and their ponies

However, what I found really interesting about the period was the number of obvious eccentrics who found horses a useful means of augmenting their eccentricity and visibility. Like any modern internet influencer, they wanted to be seen and draw the crowds. One such was the peculiar dentist and corset-maker Martin van Butchell who rode round London on a pony painted with coloured spots. He also kept the embalmed body of his first wife in his home throughout his second marriage.

Van Butchell and his long-suffering pony probably deserve a blog post to themselves, but today I’m writing about Robert Coates (1772 – 1848), actor (well, that’s how he viewed himself – opinions may differ). Coates was the son of a wealthy plantation owner from Antigua in the West Indies. From his father, he inherited a lot of money and a great love of diamonds. Fortunately, his inheritance also included dad’s diamond collection, and Coates made sure everyone knew that by wearing them in abundance on the various costumes he concocted, earning him his first nickname of “Diamond Coates”.

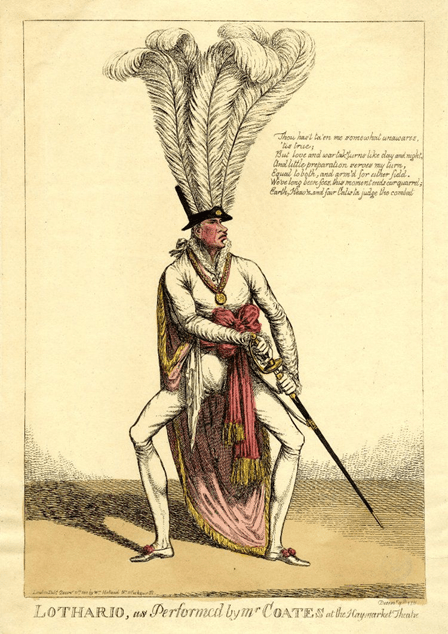

His performance of Romeo in Romeo and Juliet was so bizarre that people found it hilarious. Decked out in a blue cloak, red pantaloons and an opera hat with plumes, plus lashings of diamonds, his trousers splitting on stage only added to the amusement and earned him the enduring alternative nickname of Robert “Romeo” Coates. On one occasion, he carefully dusted the stage before going into his theatrical death throes as Romeo. Once when he lost a diamond buckle on stage, he stopped the performance and crawled about looking for it.

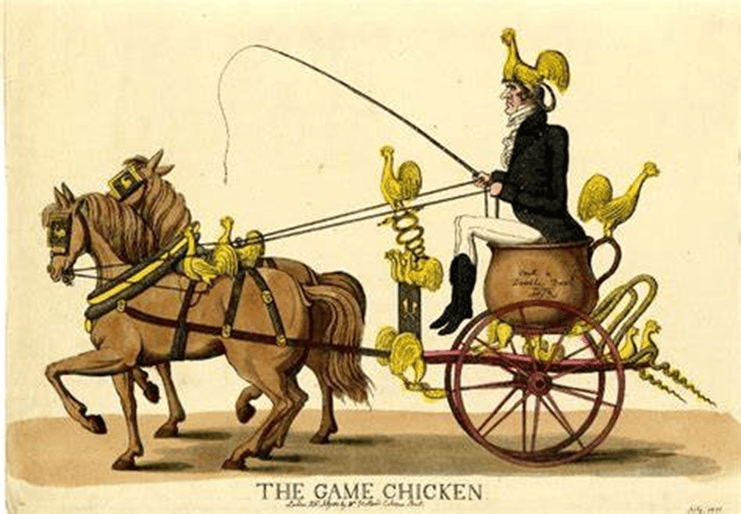

The first horsey connection comes through his fantastically decorated carriage. He usually wore furs when he went out, even in the hottest weather. His heraldic device was a crowing cock, with the legend: “While I live, I’ll crow” prominently displayed on his carriage which was drawn by a pair of beautiful ponies. Note: all true eccentrics have ponies, not horses. Or even better, Galloways or Gallowas.

Did you say Galloway?!

Those of you who follow my work will know that I am somewhat obsessed by the history of the Galloway Nag, and my Galloway radar (Gallowaydar?) went into overdrive when I came across a character in a fictional tale that seemed to be broadly based on the life of Coates – and the story had a suitably bizarre reference to Galloways.

The tale seems to have first appeared in an anonymous book titled: Richmond; or Scenes in the Life of a Bow Street Runner in 1827. Peter Haining, who included the story in his anthology Murder at the Races, attributes it to journalist Thomas Gaspey (1788-1871), who was a crime reporter for the Morning Chronicle.

The story is about horse racing in Lyndhurst in the New Forest, and refers to races between still wild local forest ponies and racehorses, which is interesting in itself. Haining produces a quote from 1859 that suggests this was a fairly regular event in the early nineteenth century: “These stirring spectacles between race horses and the forest ponies have frequently formed the subject of pictorial illustration and remained long in the imagination of those who saw them.” (William White, Gazetteer and Dictionary of Hampshire.)

A Racing Swindle: the plot

The plot of “Richmond’s”, or Gasper’s, tale revolves round a wealthy and fashionable young West Indian, Ellice Blizzard, described as “descended by the father’s side from a family of West India planters, and by the mother’s from an African princess, whom the chances of negro warfare had consigned to slavery in the British colonies”.

Whether this reflects Coates’s own family history, or what people thought about it, is not certain, but the description of Blizzard’s arrival in Lyndhurst does suggest an exaggerated version of Coates: “The first object that attracted my notice was a carriage of the most grotesque construction – an odd mixture of the antique and the modern – drawn by no less than ten horses, with five postilions in outré liveries”.

The passenger is equally imposing: “He wore a high black fur cap, shaped somewhat like a bishop’s mitre, and similar to those which I have seen worn by Armenian merchants on the exchange; but with this difference, that there was a plume of feathers stuck in the front, and supported by a knot of gaudy ribbands of many colours, like the cockade of a recruiting sergeant.”

Young wealthy eccentric Mr Blizzard has almost inevitably fallen into the hands of swindlers and crooks, who have told him that if he wishes to be truly up-to-the-minute and maintain his eccentric lead, he should now reject the fashionable races that most people attend and go to the New Forest to see the pony and racehorse contests there. Of course, this is because they see far greater opportunities to fleece him.

Galloway reindeer?!

The story reveals the tropes, language, and attitudes of the times, racial categorisation and stereotypes among them. Blizzard, having deliberately set out to forge an eccentric character, according to Gasper “had set his heart upon having a Lapland sledge drawn by reindeer; but this was an equipage all his wealth could not command. The sledge, indeed, or something called so, he might have procured in the metropolis; but the reindeer were not to be had, and they could not be manufactured even by London ingenuity, out of any other species of animal that would draw in a carriage. I have since understood, indeed, that one of Mr Blizzard’s Hebrew friends did make the attempt to transform a set of galloways into reindeer by decorating their heads with antlers, and other contrivances; but the horses could not be made into passable stags, and the attempt was abandoned, to the great grief of the Jew speculator, and the sad disappointment of Blizzard, who had to content himself with ordinary steeds for his extraordinary carriage”.

It’s heavy-handed and unsubtle humour, making play on the presumed stupidity or avarice of “foreigners”, and my reason for quoting it at all is firstly, that references to Galloways are sufficiently irregular and few that every single one has relevance. Secondly, Galloways themselves were frequently the butt of satire and humour for no other reason than being Galloways. At times they too were viewed as foreign and outlandish, particularly in England, and as being therefore an appropriate target for derision, however good they were.

Back to Robert Coates

The real Robert Coates continued to act, sometimes bribing stage managers and always causing a stir, until the crowds tired of him. He called himself the “Celebrated Philanthropic Amateur” and seems to have played it entirely straight – at least in his own mind. However, it has been suggested that he was parodying stage performances, and perhaps we should credit him as providing an early form of Monty Python-esque humour. If so, he was not just a passing oddity of the stage, but an avant-garde performer. Like many young men who inherited massive fortunes, he later in life found himself financially down on his luck.

Horses had a part in his final, macabre appearance in London. At the age of 78, he was involved in a street accident when leaving the Theatre Royal in Drury Lane. Somehow he was caught up and crushed between two horse-drawn vehicles, a Hansom cab and someone’s private carriage, dying six days later. Interestingly, the coroner called his death “manslaughter by person or persons unknown”. Did someone have it in for Robert Coates? Or was it just a case of dangerous driving? The passage of time means we will probably never know, but the streets of London were undoubtedly drabber after his death.

Miriam A Bibby January 2025